Overview of the main features and spread of the new Variant of Interest (VOI) Mu (B.1.621 and B.1.621.1) in Italy and Worldwide

Published: 29 September 2021

According to guidelines of WHO variants of SARS-CoV-2 can be classified as VOI when they present:

- Mutations that can modify the characteristics of the virus such as its transmission, ability to be recognized by the immune system, cause a form of the disease with increased severity and/or a decrease in the efficacy of diagnostic methods or therapies.

- Proven ability to cause an increase in the number of infections or outbreaks of COVID-19 at the point to represent a probable risk for public health.

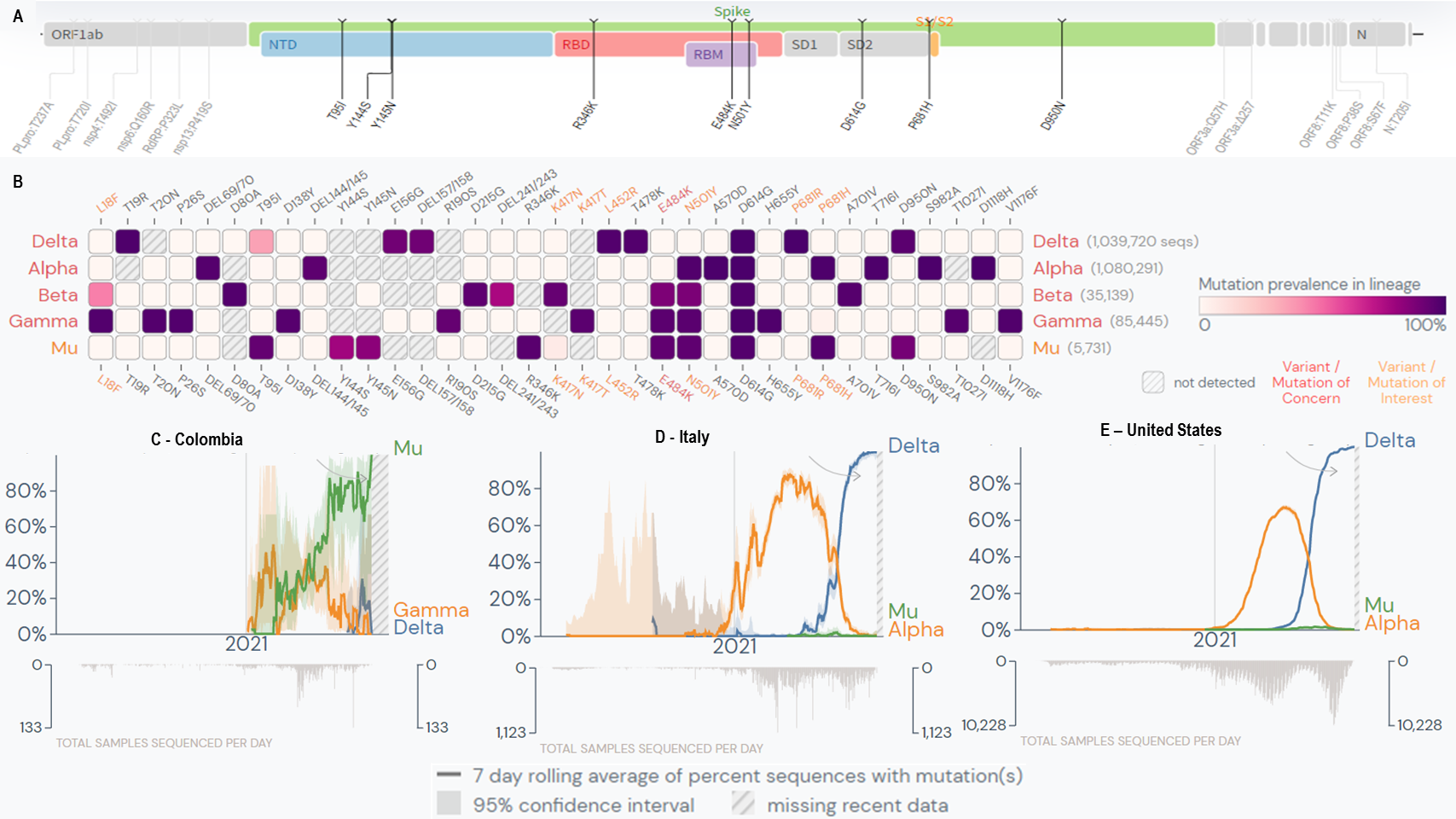

Panel B presents a comparison between the characteristic mutations of the Mu variant and the mutations typically identified in the 4§ variants of SARS-CoV-2 classified as Variants of Concern (VOC). The aim of this comparison is to highlight similarities and differences between Mu and VOCs. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) variants of SARS-CoV-2 are classified as Variants of Concern (VOC) if they satisfy the definition of VOI (see above) and present one or more of the following characteristics:

- Increased transmission or worsening of the epidemiology of COVID-19.

- Increased virulence or changing of the clinical manifestation of the disease.

- Decreased efficacy of therapies prevention measures or of diagnostic instruments, treatments and vaccines.

§With the September 3rd 2021 update, ECDC (the most important European health authority) has removed the Alpha variant from the list of the Variants of Concern. This decision was driven by the limited circulation of Alpha in the continent and its reduced impact (according to currently available data) on the efficacy of vaccination campaigns (see the following link). However, the WHO classification remains unchanged.

The first genome of the B.1.621 lineage, subsequently designated as the Mu variant, was isolated in Colombia, in the Magdalena district, during January 2021 [1].

Panel A shows that the Mu variant presents many mutations in the Spike gene, among which an insertion at 146N and a series of amino acid substitutions, such as T95I, Y144T, Y145S in the N-terminal domain, R346K, E484K and N501Y in the receptor binding domain (RBD), and P681H in the S1/S2 cleavage site [1, 2].

Panel B highlights the genomic similarities between the Mu variant and the variants classified as Variants of Concern (VOC) by WHO. These common mutations are often associated to specific characteristics; more specifically, E484K (in common with Beta and Gamma) reduces the neutralization by convalescent plasma, N501Y (in common with Alpha, Beta and Gamma) decreases the power of neutralizing antibodies and improves the infectivity. P681H (in common with Alpha and some Gamma lineages) is associated with higher infectivity and, finally, D950N (common with Delta) which function is not characterized yet [1, 3].

Preliminary studies, not subjected to revision by independent experts, indicate that Mu might have an increased ability to escape immune recognition (from both convalescent sera and vaccine induced immunity) compared with other variants, a key aspect for the success of mass vaccination campaigns [4]. However, it is important to underline that these conclusions are supported by limited data, and for this reason can not be considered solid. Further studies will be required to evaluate the biological and epidemiological impact of the mutations identified in the genome of the Mu variant [1].

In Colombia the Mu variant became prevalent during the third wave of COVID-19 (between March and August 2021) progressively replacing the Gamma variant (P.1 and derivatives) and becoming the most prevalent variant around May 2021 (panel C) [1, 3, 4].

The limited data currently available suggest that in Colombia the prevalence of the Mu variant is increasing constantly. At the same time, and unlike most countries worldwide, the prevalence of the Delta variant in Colombia is quite limited, despite the fact that Delta was isolated in the country around July 2021. This observation seems to suggest that the Mu variant might potentially compete with the most successful VOC of SARS-CoV-2 at the moment (panel C). However, it is important to note that due to the low numbers of genomes available from Colombia (a thousand for Mu and twenty for Delta) these observations are purely speculative. Moreover, as described below, contrasting observations are obtained when countries with a different epidemiological situation are considered.

On August 30th 2021 Mu was classified as a Variant of Interest (VOI) by the World Health Organization (WHO). At the time, this variant was already detected in at least 39 countries among which the United States, Spain, the Netherlands and Denmark [2, 3].

In Italy Mu was isolated for the first time in Friuli Venezia Giulia in April 2021. According to the periodical reports released by the National Institute of Health (ISS), this variant was then detected in other Italian regions such as Campania, Lazio, Tuscany, reaching its peak of prevalence in Veneto during July 2021 (panel D). Panel D also shows that Delta and Mu were observed in Italy around the same interval of time; in an epidemiological context different from that observed in Colombia. In Italy the Delta variant reached a far greater prevalence with respect to Mu and rapidly became the most prevalent variant in the country, replacing the Alpha variant. However, similarly to Colombia, these observations are based on a relatively limited number of sequences (~eighty sequences for Mu and fifteen thousands sequences for Delta) and can not be considered conclusive.

The case of the United States is probably the most interesting, since a substantial number of genome sequences are available for both the Delta and the Mu variant (two thousand five hundred and two hundred and seventy thousands respectively - panel E). Also in this case it is evident from the figure that both Mu and Delta were detected in an overlapping interval of time and that the Delta variant rapidly replaced Alpha (most prevalent variant in the USA at the time), steadily increasing its prevalence from that moment. On the contrary, the Mu variant, as also stated by reports (link) released by the Centre of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), reached its peak in prevalence in June 2021 and then steadily decreased at the point that, at the time of writing, represents less than the 0.5% of the circulating variants in the United States.

All the observations reported in this update highlight the importance of an active and efficient surveillance system for monitoring the progression of the pandemic, the appearance and spread of new lineages and/or variants, and for the evaluation of the risk that these variants represent for public health. Only through surveillance, in fact, it is possible to establish efficient methods for prevention and containment.

IMPORTANT: graphs and data reported in the present update are extrapolated from the per country reports available on outbreak.info and are updated to September 16th 2021. Outbreak.info is a project which aims to collect and unify genomic and epidemiological data about SARS-CoV-2 and then represent them in an interactive way that allows researchers to easily monitor the pandemic in real time (data are updated daily). More recent data about the countries considered in the present update are available at the following links: Colombia, Italy, United States.

Sources:

outbreak.info (images and epidemiological data),

WHO and ECDC (Variants of Interest and Variants of Concern),

ISS (epidemiological data of Italy),

CDC (epidemiological data of the United States),

[1] “Characterization of the emerging B.1.621 variant of interest of SARS-CoV-2”. Katherine Laiton-Donato et al. 21 July 2021,

[2] “A cluster of the new SARS-CoV-2 B.1.621 lineage in Italy and sensitivity of the viral isolate to the BNT162b2 vaccine”. Serena Messali et al. 27 July 2021,

[3] “Ineffective neutralization of the SARS-CoV-2 Mu variant by convalescent and vaccine sera”. Keiya Uriu et al. 7 September 2021 (preprint),

[4] “The impact of vaccination strategies for COVID-19 in the context of emerging variants and increasing social mixing in Bogotá, Colombia: a mathematical modelling study”. Colombia Guido España et al. 7 August 2021 (preprint)